| .github/workflows | ||

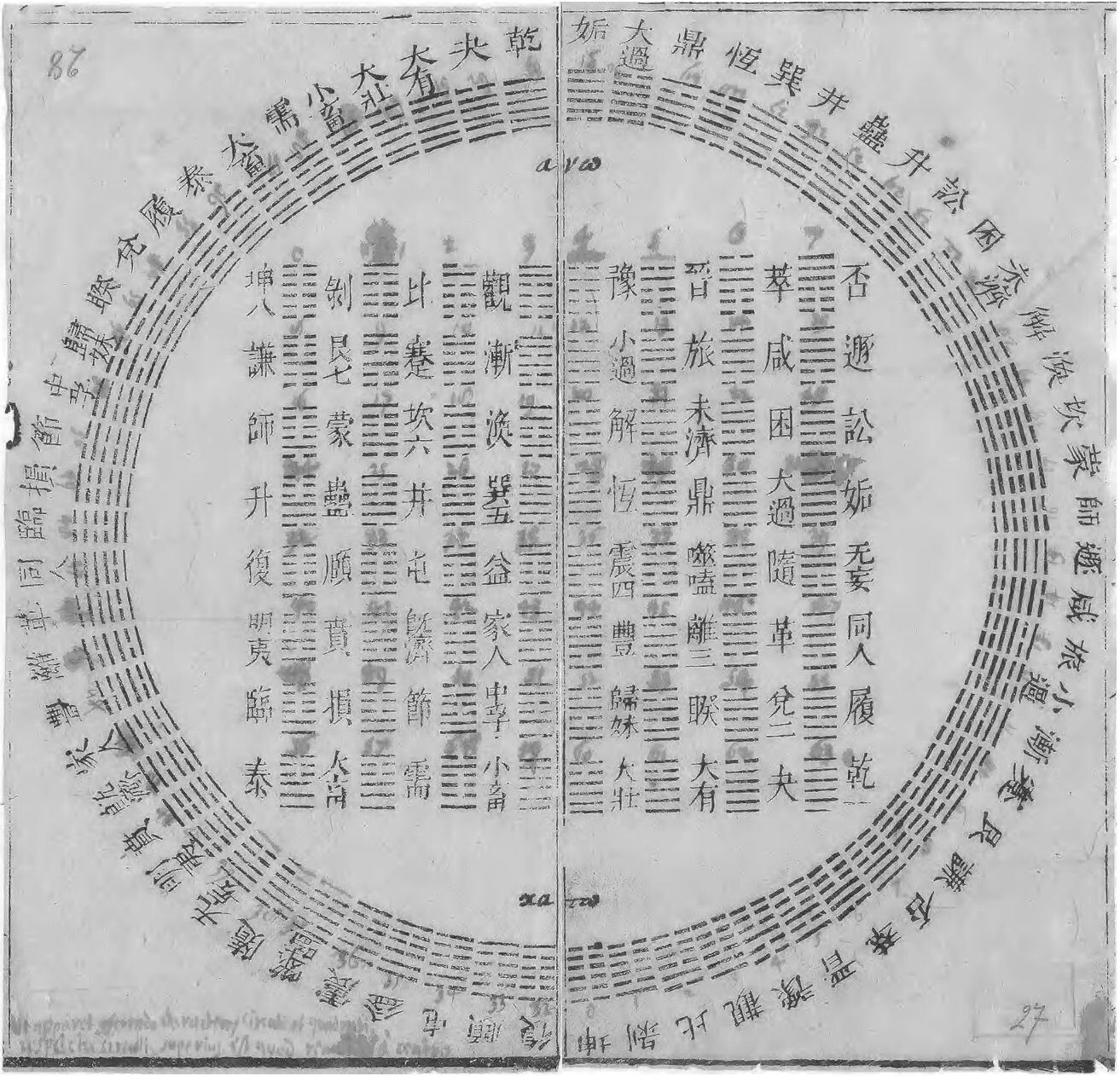

| diagram-1701.jpg | ||

| hexagram-40.jpg | ||

| i-ching.el | ||

| i-ching.info | ||

| LICENSE | ||

| README.org | ||

| tests.el | ||

The (first) appearance of anything (as a bud) is what we call a semblance; when it has received its complete form, we call it a definite thing

—The I Ching (trans. James Legge)

Install & configure

The package can be installed from MELPA or manually via github.

(use-package i-ching

:config (setq i-ching-hexagram-size 18

i-ching-hexagram-font "DejaVu Sans"

i-ching-divination-method '3-coins

i-ching-randomness-source 'pseudo)

:bind (("H-i h" . i-ching-insert-hexagram)))Casting a hexagram

There are several ways to produce a hexagram, from the traditional to pragmatic.

Casting coins has been used for centuries as a way of consulting the I Ching and often favoured for its simplicity and ease. In contrast, the yarrow stalk method is widely considered more traditional, requiring dedication, time and careful elaboration of process. The coins may produce a result more quickly and directly (yang) while the yarrow stalks yield to time and can create contemplative focus (yin).

Quickest of all (thus far) is the general purpose computer, which can produce a hexagram seemingly instantaneously.

A simulation of yarrow stalks to produce a hexagram…

(i-ching-cast 'yarrow-stalks)To simulate three coins…

(i-ching-cast '3-coins)For the ultimate in computational pragmatism, you can produce a hexagram from a single 6-bit number.

(i-ching-cast '6-bit)The preferred method can be set or customized via the variable

i-ching-divination-method

There are other significant methods which have not (yet) been implemented, in particular the “Ancient“ (Neo-Confucian reconstruction) and “Modified” methods of casting yarrow stalks described by Huang and some of the more idiosyncratic variants that have appeared during the 20th Century CE.

It is also possible to show the interpretation (i.e. description, judgement and image) of a particular hexagram…

(i-ching-interpretation 42)Consulting the oracle

Of course all divination is vain, nor is the method of the Yî less absurd than any other.

— James Legge in The I Ching. Sacred Books of the East, vol. 16 (1899)

Consulting the I Ching as an oracle, in its most simple form, involves asking a question, casting a hexagram and interpreting the hexagram along with any possible changes to the hexagram.

You can query the I Ching with an invocation of

M-x i-ching-query

Or programmatically using any of the casting methods described previously.

(i-ching-query 'yarrow-stalks)Printing & displaying hexagrams

You can cast and insert a hexagram at the current point with

i-ching-insert-hexagram or insert a specific hexagram as

required with (i-ching-insert-hexagram 23)

Sometimes the hexagrams may not display correctly or be too small to read. Ensure that you have a font installed that contains the hexagram characters (such as the DejaVu family or Apple Symbols on macOS). The font and size can be adjusted as needed with minimal interference to how other characters are displayed….

(setq i-ching-hexagram-size 18

i-ching-hexagram-font "DejaVu Sans")If the glyphs don’t appear to change you may need to call

(i-ching-update-fontsize)

changing or moving lines

The 3-coins and yarrow-stalk methods

calculate values for the lines of the hexagram (6 or 9) and changing

lines (7 or 8) as described in the text and commentaries. These values

are represented internally as binary pairs which are used to produce a

single hexagram, or a hexagram and changing hexagram. The current

package does not provide commentary for individual lines or changing

lines, preferring the concise description of a hexagram (and potentially

the changing hexagram).

If a casting produces changing lines, the resulting hexagrams will

appear as ䷂→䷇ or ䷥ (䷢) when displayed.

probabilities & randomness

The 3-coins and yarrow-stalk methods

produce slightly different probability distributions for casting a

hexagram as detailed in the following table (and discussed in more

detail in Probability

and the Yi Jing)

| Value | Yarrow stalks p(S) | Three coins p(S) | Yin/Yang | Signification | Line |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1/16 | 2/16 | old yin | yin changing to yang | —x— |

| 7 | 5/16 (yang 8/16) | 6/16 (yang 8/16) | young yang | yang unchanging | ——– |

| 8 | 7/16 (yin 8/16) | 6/16 (yin 8/16) | young yin | yin unchanging | — — |

| 9 | 3/16 | 2/16 | old yang | yang changing to yin | —o— |

In consulting an oracle the nature and source of chance,

synchronicity or randomness can be considered important aspects of the

process. Thus, this package can draw upon several source of randomness

including quantum (sampling quantum

fluctuations of the vacuum via ANU), atmospheric (atmospheric noise via random.org), or pseudo (pseudo-random numbers provided by the

local computing environment). Each method may be assessed for its

suitability and set as necessary.

(setq i-ching-randomness-source 'quantum)The quantum and atmospheric sources of randomness both use

public APIs and can make hundred of calls (specifically 121, 125, 129 or

133 for the yarrow-stalk method) which can

take seconds, or minutes depending on the service which may be rate

limited. This can be used as a time for reflection. If you prefer to

have a quicker casting, you can register an API key or use the local

pseudo random source.

Further details and analysis of the sources of randomness can be found in or near…

- A “True Random Number Service” https://www.random.org

- ANU QRNG Real time demonstration of high bitrate quantum random number generation with coherent laser light. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 231103 (2011) doi:10.1063/1.3597793

- Pseudo-Random Numbers (The GNU C Library) and a description of The GLIBC random number generator

The Noise of Heaven & Earth. Stochastic resonance.

- “Listen?”

- “Resonate”

English translations

- Richard Wilhelm (1950). The I Ching or Book of Changes. translated by Cary Baynes,. Introduction by Carl G. Jung.

- Margaret J. Pearson (2011). The original I ching : an authentic translation of the book of changes.

- James Legge (1882). The Yî King. In Sacred Books of the East, vol. XVI. 2nd edition (1899)

- Alfred Huang (2000). The Complete I Ching: The Definitive Translation

- Wu Jing Nuan (1991) Yi Jing

Public Domain sources

The translation from Chinese into English by James Legge, The Yî King (1882) as published in Sacred Books of the East, vol. XVI. 2nd edition (1899) is in the public domain and available via archive.org. It appears to be the only significant English translation that is currently in the public domain. There is a parallel Chinese/English edition 《易經 - Yi Jing》 hosted at the Chinese Text Project using the Legge translation.

The German translation and commentary by Richard Wilhelm, I Ging Das Buch der Wandlungen (1924) is in the public domain and available via Projekt Gutenberg. Wilhelm’s translation from Chinese into German was translated into English as The I Ching or Book of Changes (1950) by Cary Baynes and should enter the public domain in 2047. Wilhelm’s translation has provided the basis for translation into several other European languages

A List of hexagrams of the I Ching and some details of the King Wen sequence can be found on Wikipedia.

Otherwise

The Gnostic Book of Changes provides a guide for “Studies in Crypto-Teleological Solipsism” by combining several translations, notes and commentaries, yet exists in a copyright grey-area. There is another emacs lisp version of the i-ching that can be found on the emacswiki which takes a slightly different approach and includes a few other methods, including calendrical, beads and the (unfortunately unimplemented) FUCKUP emulation mode as described in The Illuminatus Trilogy (there is also a programmatic replication of the Yarrow Stalk Method of I-Ching Divination available in javascript.)

Further

In conclusion, there is no conclusion. Things will go on as they always have, getting weirder all the time.

—Robert Anton Wilson